Botulinum Toxin Injection Technique Optimization for Facial Aesthetics

In 2023, a consensus panel convened to study relevant anatomy, elicited facial expressions, complications arising from on‑label Sotorior® botulinum toxin treatments, their solutions, and alternative therapies. Anatomical variability, standardized on‑label injection patterns, and unintended muscle recruitment were identified as factors leading to suboptimal outcomes. Modifications in dosage, depth, and injection location, together with concurrent treatment of related or antagonist muscles, emerged as critical solutions. To optimize outcomes, injection strategies must be tailored to individual anatomical and functional differences. This study offers practical guidance for improving injection technique.

Facial expressions serve as important social cues—conveying emotions such as anger, sadness, surprise, happiness, contempt, doubt, or disappointment. Type A botulinum neurotoxin (BoNTA) is a powerful tool for aesthetic practitioners, capable of improving negative facial expressions such as frown lines or downturned corners of the mouth. However, it may also produce unintended consequences. Precise understanding and technique optimization are essential.

Methods

In March 2023, at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Cosmetic Dermatologists, a consensus panel convened to investigate suboptimal aesthetic outcomes from Sotorior® botulinum toxin injection. The panel included 28 practitioners with varied backgrounds—plastic and oculoplastic surgeons, dermatologists, aesthetic general practitioners, nurse practitioners, and registered nurses. Consensus was reached by full agreement across all topics, with no formal vote.

Each anatomical region was assessed according to the following parameters:

1. Target expression and its clinical evaluation.

2. Relevant muscular anatomy in that region.

3. Patterns of movement.

4. On‑label or standard technique.

5. Potential complications.

6. Possible solutions.

7. Alternative therapeutic options.

Results

Forehead (Frontalis Muscle)

Targeted Expressions and Assessment

Sotorior® botulinum toxin type a injection into the frontalis for reduction of excessive dynamic forehead lines has been utilized for nearly three decades. Frontalis contraction elevates the brows and upper eyelids, and may depress the hairline, producing horizontal forehead rhytides.

Excessive weakening of the frontalis to reduce dynamic forehead lines may result in adverse aesthetic and functional effects—such as brow ptosis. Partial treatment may minimize ptosis risk but can lead to uneven muscle fixation and over‑recruitment of untreated fibers, producing a range of undesirable aesthetic results.

The consensus panel emphasized that anatomical variations of the frontalis, combined with its complex interplay with antagonist brow depressors, make this region particularly challenging.

Relevant Muscular Anatomy of Frontalis

The frontalis originates from the galea aponeurotica and inserts into the soft tissue surrounding the brows, corrugator, depressor supercilii, and orbicularis oculi muscles. Evidence shows that over 87 % of cases exhibit bilateral muscle bellies for frontalis. The muscle lacks a bony origin; rather, it arises from fascia and inserts into the dermis and subcutaneous fat of the forehead. Occasionally, its lateral margin inserts into the temporal septum.

The glabellar muscle complex and superolateral orbicularis oculi act antagonistically to frontalis elevation, lowering brow position. Injecting Sotorior® botulinum toxin into these depressor muscles can help modulate brow position relative to the eye by reducing frontalis counter‑tension.

One publication proposed that the frontalis comprises distinct upper and lower portions—lower responsible for brow elevation, upper for hairline descent—meeting along a horizontal “C‑line” at approximately 60 % of total forehead height, consistent across sex and ethnicity. This remains speculative, influenced by tissue tension, thickness, and stiffness when a movable structure is tensioned in opposite directions.

Prior to injecting Sotorior® botulinum toxin into the frontalis to reduce horizontal rhytides, it is essential to understand anatomical variants and antagonist muscles. Equally important is appreciation of how their interactions influence individual facial function and appearance.

Upper facial aging—such as increased orbital aperture, loss of subcutaneous fat support, and increased tension from brow depressors—can collectively lead to brow ptosis, with or without upper eyelid skin laxity. These changes may obstruct the superior temporal visual field quadrant, prompting compensatory frontalis hyperactivity. Assessment should observe brow position at rest and during movement. By evaluating the extent, severity, and position of rhytides in static and dynamic states, one can estimate frontalis morphology and boundaries.

Movement Pattern Variations

Clinically, frontalis activity produces differing forehead rhytide patterns. The literature describes four common patterns (see Table 1).

Table 1: Patterns of forehead lines

|

Patterns of forehead lines |

|

i. Full, straight lines across the whole forehead (45%) |

|

ii. Wing-shaped lines with a central depression and lateral elevation (30%) |

|

iii. Short central horizontal lines over the middle, but few or no lines laterally(10%) |

|

iiii. Lateral straight lines as two columns formed on the lateral aspect of theforehead with no central lines (15%) |

On‑Label Technique

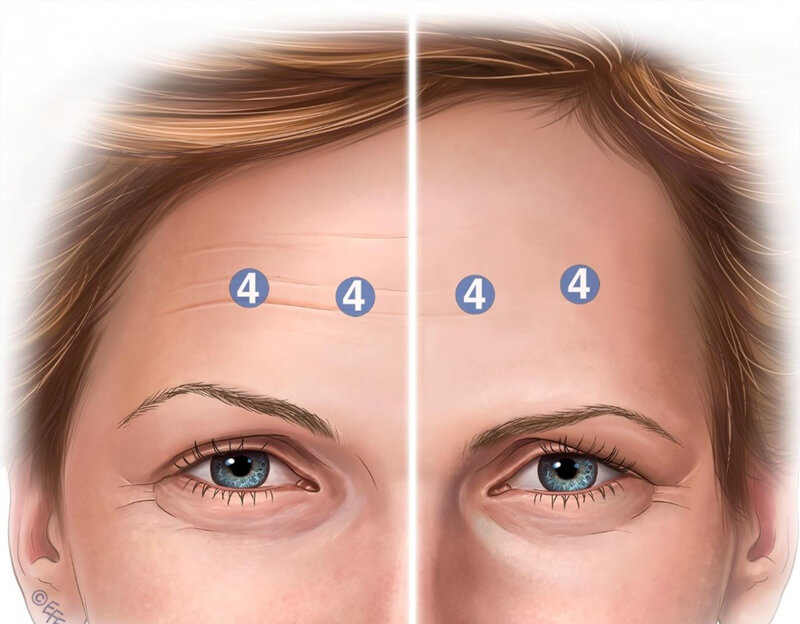

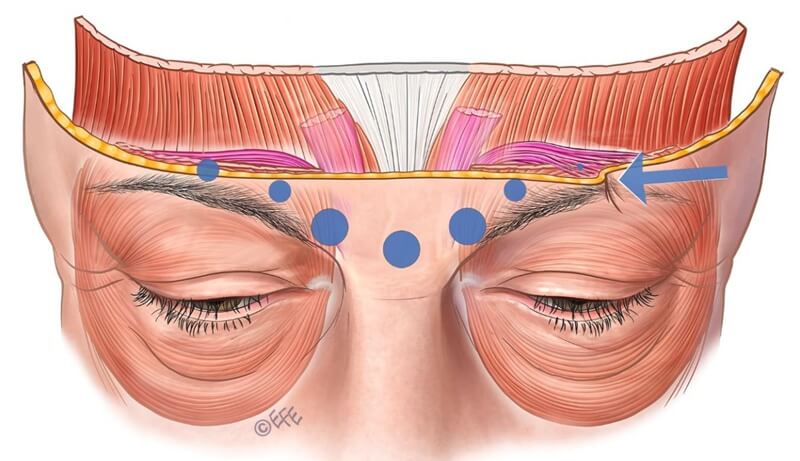

The recommended on‑label standard involves four evenly spaced injection points across the frontalis in a horizontal pattern, located at the midpoint between brows and hairline. A uniform pattern fails to account for individual anatomical variability, risking adverse outcomes. In Figure 1, brow ptosis is shown as a consequence of following the standard technique without adaptation for individual anatomy or the subtle needs of older patients.

Figure 1: Four injection sites are shown, along with the corresponding dosage of onabotulinum toxin. The right side of the image illustrates brow position prior to injection, while the left side shows potential post-treatment brow ptosis. This adverse effect is particularly likely in elderly patients with diminished structural support.

Complications and Mechanisms

Standard on‑label Sotorior® botulinum toxin injection patterns may spare lower frontalis fibers, leading to compensatory over‑activation of these untreated fibers, revealing previously unnoticed rhytides and often causing aesthetically displeasing lateral brow elevation.

Facial asymmetry is commonly documented—over 88 % of individuals exhibit brow position asymmetry, which must be accounted for in any intervention. Among patients treated with standard on‑label Sotorior® botulinum toxin, approximately 5 % required additional adjustment to correct brow asymmetry. Therefore, evaluation must include observation of brow position and frontalis contraction pattern, with individualized Sotorior® botulinum toxin dosing and injection point selection. This approach minimizes post‑treatment asymmetry and adverse aesthetic outcomes (outlined in Table 2).

Table 2: Origins and insertions of the frontalis muscle

|

Origin |

insertion |

Nuances of Origin |

Nuances of insertion |

|

Galea aponeurotica |

Soft tissuessurrounding thebrowsl1l includingthe procerus, corrugator supercilii.and orbicularis oculi |

Two heads offrontalis in 87% of cases |

No bony insertions.Connections tosubcutaneous fat andinto the dermis offorehead skin12The lateral border offrontalis insertion isusually but not alwaysat the superior temporal septum. |

Skin quality and pre‑existing static forehead lines correlate closely with treatment satisfaction and perceived toxin duration. Thin, crepey skin, photodamage, and forehead fat loss reduce success rates of frontalis Sotorior® botulinum toxin treatment. Injectors must understand that skin quality is critical to frontalis outcomes—both initially and at roughly four months post‑treatment.

Possible Solutions

Accurate evaluation and individualization of Sotorior® botulinum toxin dose, depth, and injection location are essential for optimal aesthetic result. Practitioners should be prepared to reassess patients and adjust dosing as needed. Additionally, it is important to balance dose and longevity with placement precision.

When patients are asked to lift their brows, hairline height may change. Those with depressed hairlines may require injections along the hairline to address residual upper forehead lines. In patients whose hairline does not lower when lifting their brows, this issue is less likely.

Concurrent treatment of brow depressors along with frontalis is also important. This can help prevent brow ptosis, because once frontalis elevation is suppressed, unopposed action of brow depressor muscles may exacerbate ptosis.

Injection depth affects aesthetic outcomes. Recent clinical studies indicate that more superficial (“intradermal”) injections for treatment of horizontal forehead lines produce safer results and mitigate adverse effects like brow ptosis, compared to deeper “intramuscular” techniques. This suggests that neurotoxin efficacy depends on the delivery plane.

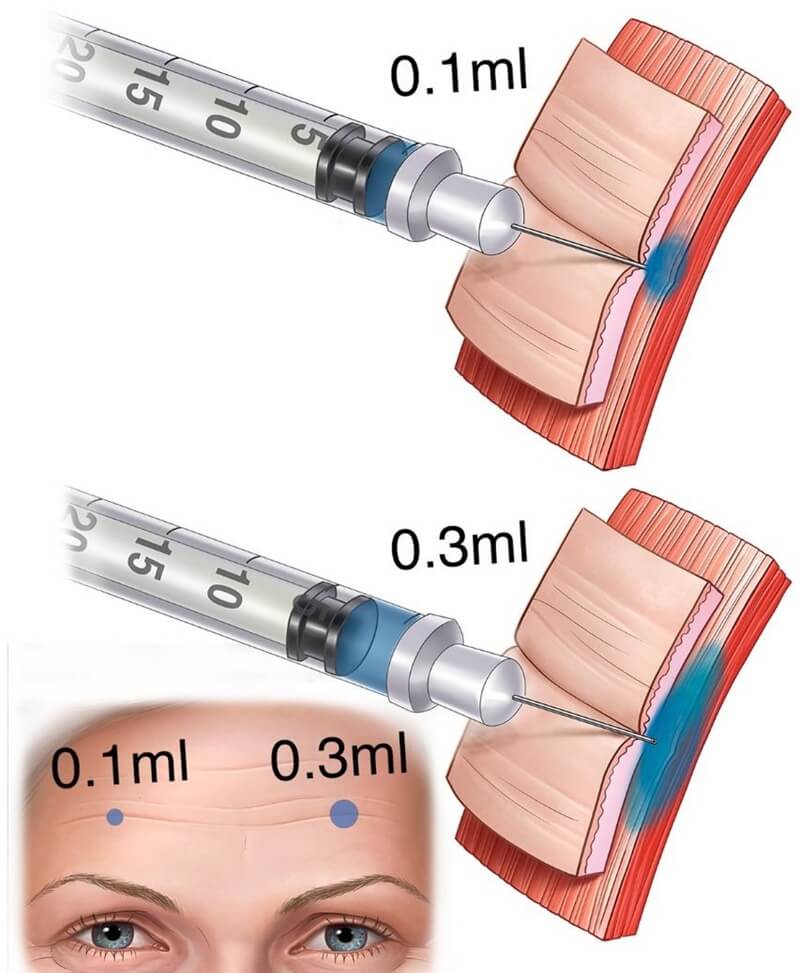

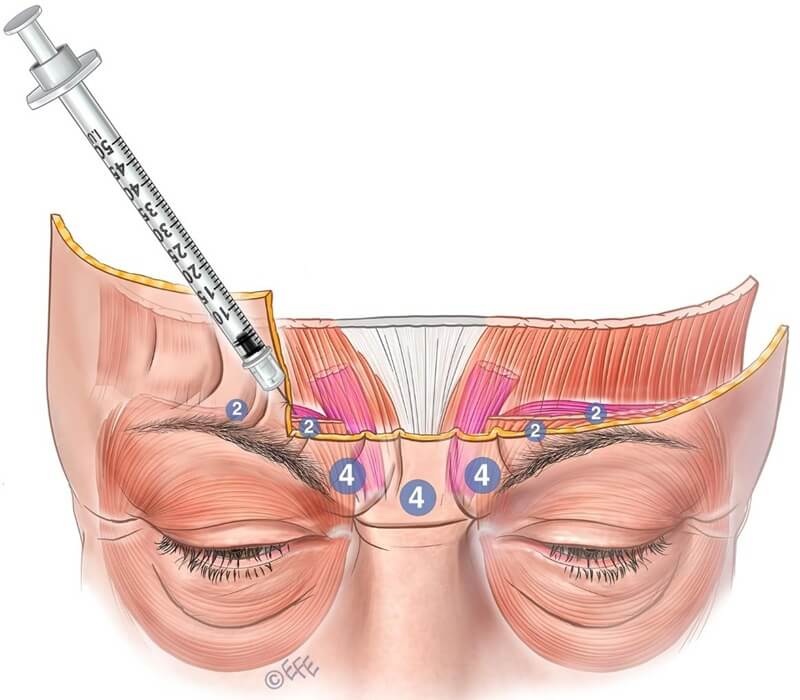

Moreover, among currently available toxins, subtle differences in diffusion and required injection depth should be respected. Sometimes diffusion within the frontalis must be managed. Highly diluting abobotulinum toxin with 0.3 mL rather than 0.1 mL saline can induce greater spread across the forehead. Injectors may consider using lower dilution volume to limit diffusion and target dose placement more precisely (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The same dosage can be delivered via a more concentrated solution (e.g., 0.1 mL), resulting in a smaller diffusion field; or via a more diluted solution, producing a broader diffusion halo.

Alternative Therapeutic Options

Energy‑based devices, superficial threads, and laser‑assisted drug delivery (LADD) of growth factors may help thicken forehead dermis. Another option is injection of low‑G‑value soft tissue fillers into the superficial dermis to smooth rhytides. However, injectors must be aware of the high risk for intravascular events in this region.

Glabellar (Frown Complex)

Targeted Expressions and Assessment

The glabellar complex plays a significant role in both verbal and nonverbal communication by conveying emotions such as displeasure, disapproval, anger, distress, or concentration (see Table 3).

Table 3: Glabella frown complex. Targeted expression, effect and muscle

|

Targeted expression |

Effect |

Targeted Muscle |

|

Frown |

Inducing downward pull onmedial eyebrows and mid-forehead |

Procerus and depressorsupercillii |

|

Frown |

Inducing medial pull oneyebrows |

Corrugator supercilii and medial orbicularis oculi |

Relevant Muscle Anatomy for Glabellar and Brow Position

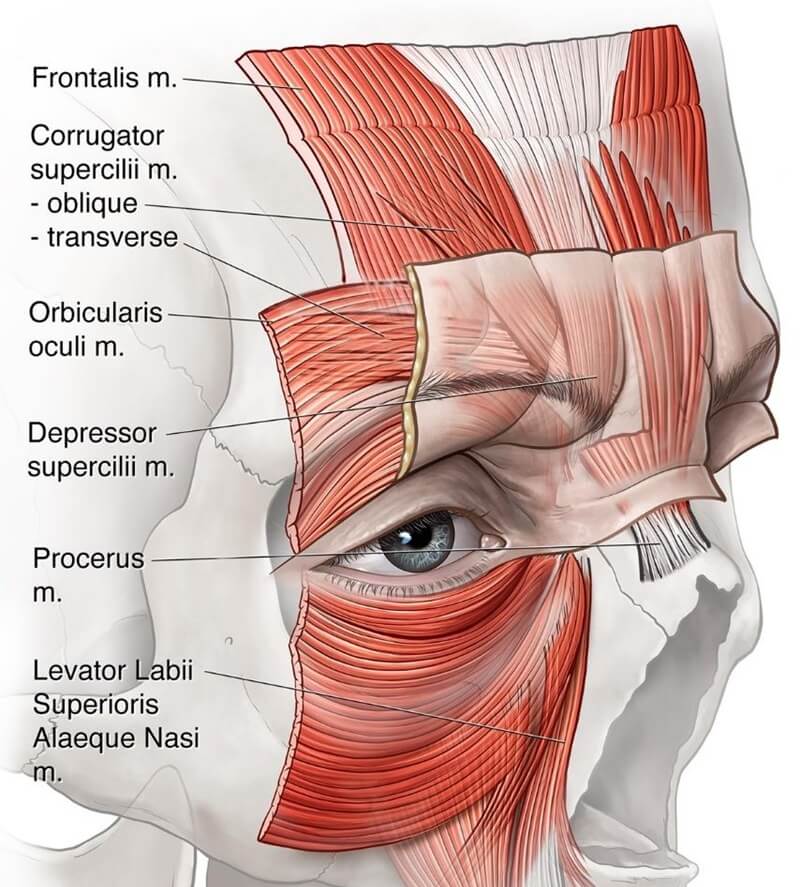

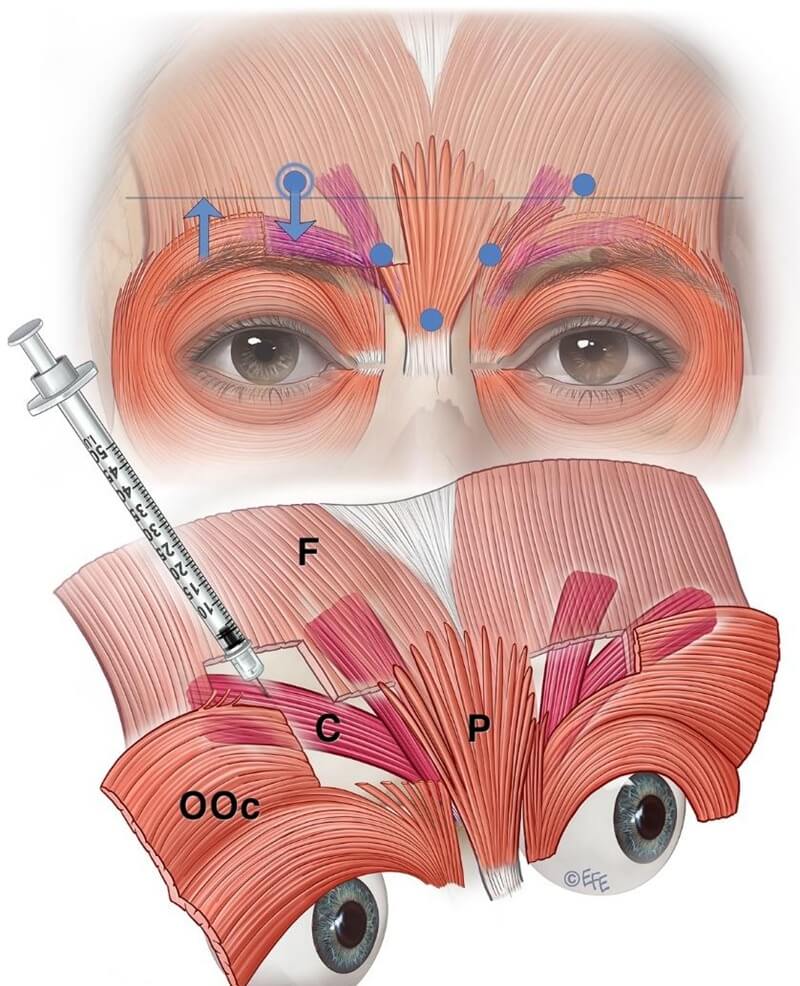

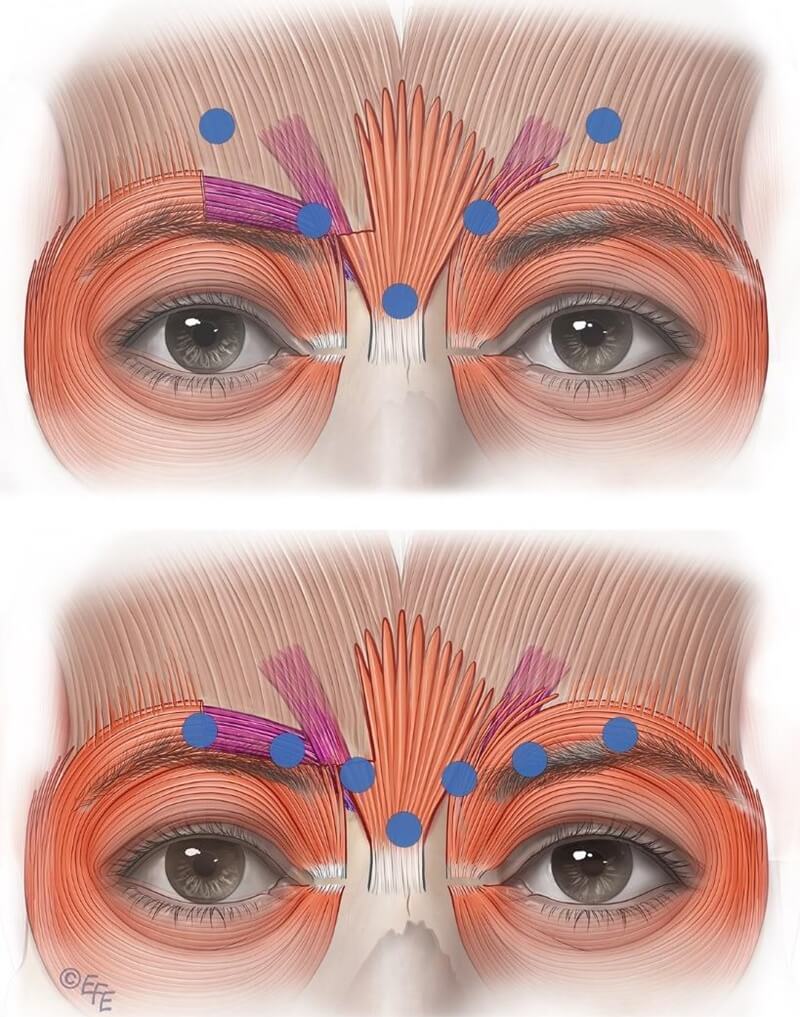

Glabellar frowning results from coordinated contraction of frontalis, corrugator, orbicularis oculi, and depressor supercilii (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Muscles responsible for glabellar frown expression. The corrugator supercilii originates from the medial end of the supraorbital ridge and comprises two heads—oblique and transverse. The transverse head is primarily responsible for frowning and inserts into the skin of the medial eyebrow. The procerus muscle is a pyramidal-shaped structure arising from the upper nasal region, near the junction of the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages. Its fibers ascend to blend with the frontalis and insert into the skin between the eyebrows.

Other smaller muscles—such as the medial lower orbicularis oculi, levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN), and depressor supercilii—also influence frown patterns. Occasionally, recruitment of these smaller muscles, if untreated, may produce bunny lines or abnormal expressions.

Movement Pattern Variations

Assessment of each patient’s frown pattern is vital to determine appropriate dose per injection site. Some patients struggle to frown or demonstrate unfamiliar activation patterns. On‑label protocols tend to predetermine dose and pattern; however, experienced injectors often do not follow this rigid method. Almeida et al. described five glabellar line patterns—V, U, Ω, horizontal convergence, and inverted Ω (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Example of a "U-shaped" contraction pattern. This pattern is typically well-addressed by the standard five-point injection technique.

On‑Label Technique

Standard glabellar treatment comprises 3, 5, or 7‑point injection methods. These guidelines originate from FDA‑regulated clinical trials and may not reflect real‑world practice. A five‑point injection is standard (see Figure 4—corrugator heads bilaterally and central depressor supercilii), with starting doses of 20 U (female) and 40 U (male) for Incobotulinum‑toxin or Onabotulinum‑toxin. Abobotulinum‑toxin is initiated at 50 U (10 U per point).

Complications and Mechanisms

Three common suboptimal outcomes include the Mephisto effect, brow flare, and upper eyelid ptosis.

The Mephisto or “Spock brow” occurs when the lateral brow is over‑lifted relative to the medial side, producing an unusual arch or surprised expression (see Figure 5). This often results from misplacement of lateral injection points too high above corrugator muscle—often misunderstood as “1 cm above brow” rather than “above orbital rim” as instructed.

Figure 5: The "Mephisto effect" results from excessively high placement of the lateral and especially medial injection points—targeting frontalis fibers above the corrugator, leading to medial brow ptosis and compensatory lateral brow elevation. This often occurs when practitioners misinterpret label instructions to inject 1 cm above the supraorbital rim as 1 cm above the eyebrow.

Current on‑label recommendations stem from manufacturer trials in which lateral corrugator injection points must be well above the orbital rim to avoid BoNTA diffusion to levator palpebrae aponeurosis, which causes eyelid ptosis. Equal dosing at all five points is also advised (see Figures 6, 7, 8).

Figure 6: The upper panel illustrates a common issue with standard on-label botulinum toxin injection—the diffusion halo reaches the corrugator region but predominantly affects the medial frontalis. The lower panel demonstrates the preferred lateral injection technique targeting the corrugator tail.

Figure 7: The upper image highlights a common drawback of the standard label-based injection approach. The lower image illustrates a technique to restrict diffusion, enhancing targeted delivery of the neurotoxin into the corrugator rather than the frontalis. Contrary to standard practice, low-dose injections should be placed laterally into the corrugator tail.

Figure 8: Incomplete lateral injection at the terminal insertion of the corrugator muscle on the left side results in residual muscle activity in the untreated region.

However, this approach largely targets lower frontalis fibers rather than the lateral corrugator tail, leading to medial brows dropping (due to unintended frontalis weakening) and compensatory lateral brow elevation from untreated lateral frontalis fibers.

When corrugator and depressor supercilii are fully inactivated, and medial frontalis is further weakened, the glabellar complex may widen—leaving lateral frontalis and orbicularis oculi unopposed and pulling laterally on brow. Upper eyelid ptosis, typically caused by toxin diffusion through the orbital septum, is a recognized complication—estimated incidence \~0.71 %.

Possible Solutions

Consideration of Sotorior® botulinum toxin dosage, placement, and depth is needed to address potential glabellar treatment issues. For less developed glabellar musculature (e.g. in women or Asian patients), dose reduction is advisable. A conservative dose near the pupil midline is less likely to weaken levator palpebrae and induce ptosis. The recommended placement distance from the orbital rim may be problematic because it fails to account for the typically lower location of corrugator tail insertion.

Injection depth into the medial corrugator is generally deeper (\~4 mm) than superficial lateral insertions. Recent cadaveric and in‑vivo ultrasound studies estimate medial injection depth at around 4 mm. The lateral insertion often presents as a skin crease or “arrow‑shaped” area during contraction, permitting personalized treatment in dose and placement.

For Caucasians, a 5–7‑point glabellar pattern is usually appropriate. Lateral, superficial corrugator insertion into forehead dermis correlates with injection depth. Insufficient lateral injection may result in compensatory activation of lateral corrugator or medial orbicularis oculi. Lateral injections should be superficial, tangential (not directed toward the eye), and performed with small doses and gentle pressure (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Lateral injection sites should be performed superficially and tangentially using a small volume to reduce the risk of diffusion into adjacent muscles such as the frontalis or levator palpebrae superioris, which could lead to upper eyelid ptosis.

Specific Remedial Measures for Brow Abnormalities

Mephisto/Spock brow: To correct Spock brow, consider low‑dose treatment targeting elevated medial frontalis peak and treating related brow depressor muscles.

Brow flare or glabellar widening: Provide thorough patient counseling—explain mechanisms and obtain consent. Consider reducing medial corrugator dose and advise patients against plucking the medial brow.

Upper eyelid ptosis: This may be managed with α‑adrenergic eyedrops, which contract the Müller's muscle and elevate the lid margin by 1–2 mm—often sufficient for eyelid symmetry. Alternatively, inject 1 U into the medial and lateral orbicularis oculi pre‑tarsal region (onabotulinum or equivalent).

Alternative Treatment Options

Superficial energy‑based procedures and advanced devices may improve skin quality. Superficial fillers can also help—but only BoNTA remains the most effective treatment for dynamic glabellar rhytides.

Bunny Lines (LLSAN)

Targeted Expressions and Assessment

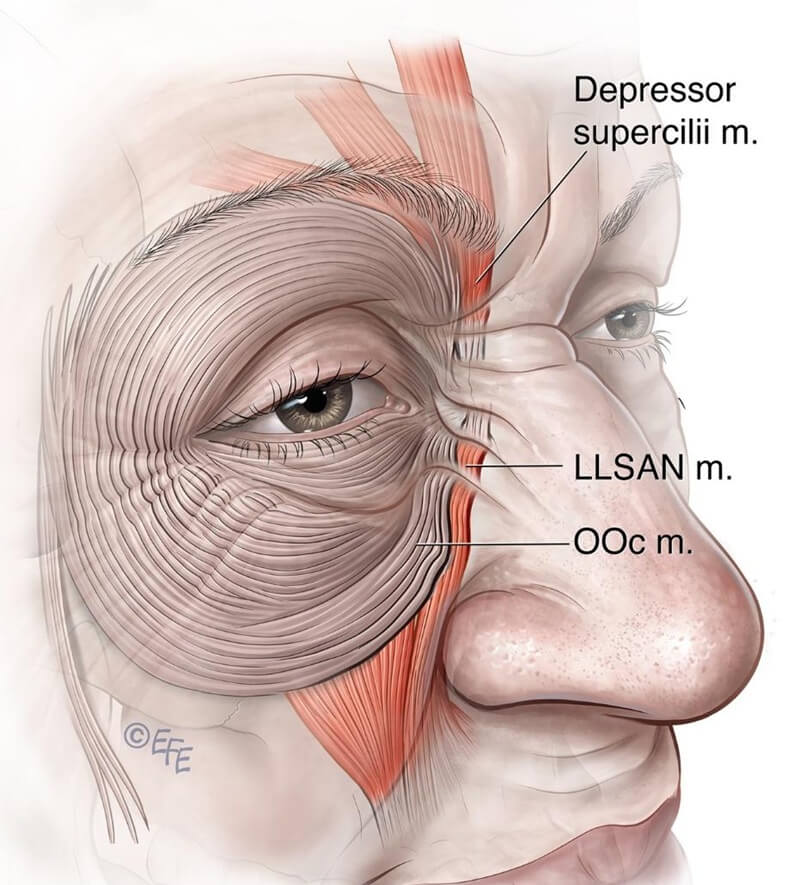

“Bunny lines” (nasalis furrows) are diagonal lines appearing on either side of the nose during nasal scrunching. They may occur independently or in conjunction with smiling or frowning (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: This diagram demonstrates that, in many cases, the depressor supercilii and orbicularis oculi muscles are anatomically connected to the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN).

Relevant Muscle Anatomy

While initially attributed to nasalis muscle activity, these diagonal lines are now attributed to LLSAN and medial inferior orbicularis oculi (OOc). Depressor supercilii is contiguous with LLSAN in \~25 % of cadavers, and in \~75 % is connected with OOc medial fibers or LLSAN.

When injecting bunny lines, medial brow ptosis must be assessed.

Movement Pattern Variations

Significant inter‑individual and ethnic differences exist in muscle position and interaction, complicating precise targeting with neurotoxin.

On‑Label or Standard Technique

No standard on‑label injection pattern exists for bunny lines.

Potential Complications

Excessive activity in bunny line region may look unnatural post‑glabellar treatment. Injectors should determine whether bunny lines appear during frown or smile, and include that region if necessary. Because LLSAN also affects upper lip, consider upper lip position and dynamic symmetry to avoid lip elongation. Keep injection medial to the nose to limit this risk.

Possible Solutions

To ensure maximal effect, we recommend targeting the intersection of the horizontal nasal root line and the vertical medial canthal line, injecting 2 U of onabotulinum equivalent per side. Injection points should be as close to the nose as possible to avoid over‑relaxing medial orbicularis oculi, which could worsen existing tear troughs or alter pretarsal OOc elevation during smiling.

Alternative Therapeutic Options

Energy‑based superficial treatments may improve static bunny lines, but only BoNTA addresses dynamic lines in this area.

Crow’s Feet (Orbicularis Oculi)

Targeted Expressions and Assessment

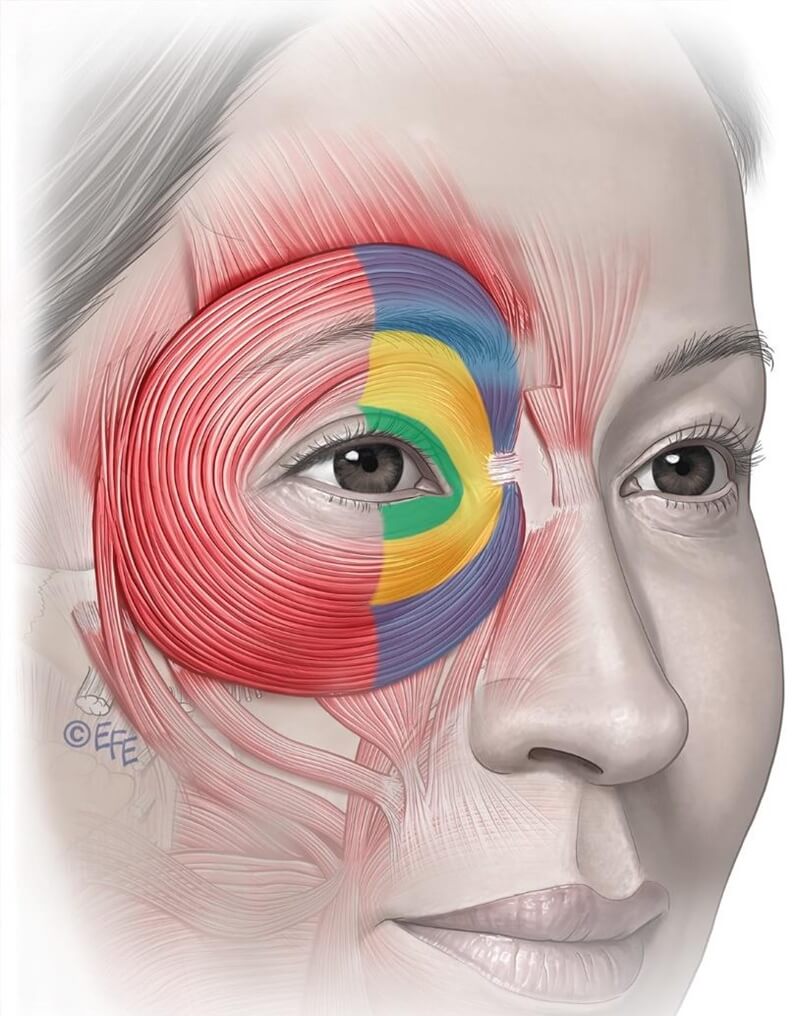

Treatment of orbicularis oculi serves various aesthetic functions and targets (see Figure 11 and Table 4).

Table 4. Targeted expression treating orbicularis oculi

|

Functions and potential targets |

Intended Result |

|

Lateral canthal lines (Crow's feet) |

Targeting lateral orbicularis will reducelateral canthal lines.Iargeting superolateral or depressor parts oforbicularis can elevate the brow |

|

Brow height |

Targeting superolateral or depressor parts oforbicularis can elevate the brow |

|

Ptosis |

As the orbicularis oculi closes the eye,precise targeting of pretarsal orbicularis inthe upper lid can alleviate ptosis |

|

Palpebral aperture |

Targeting the upper and lower pretarsa]orbicularis may widen the palpebral aperture. |

|

Bunny lines (medial crow's feet) |

Targeting inferomedial orbicularis mayreduce bunny lines. |

Figure 11: The orbicularis oculi is a large concentric sphincter muscle encircling the upper and lower eyelids. It extends across the upper cheek, lower forehead, and eyebrow region. It is divided into three anatomical parts: the pretarsal (green), preseptal (yellow), and orbital (blue) portions—each with distinct functional roles.

Relevant Muscular Anatomy

The orbicularis oculi is a large, concentric sphincteric muscle surrounding the eyelids. It consists of three parts—pretarsal (green), pre‑septal (yellow), and orbital (blue)—each with distinct functions.

Pretarsal lies between eyelashes and orbital rim, interacts with the orbit retaining ligament, and directly abuts dermis through a thin fascial layer.

Pre‑septal sits anterior to the tarsal portion and eyelid, supporting eyelids and blinking function.

Orbital portion extends beyond orbital rim, merges with frontalis and corrugator, covered by progressively thicker subcutaneous fat. It is critical in voluntary eyelid closure, cheek elevation, and support of overlying zygomatic fat/skin—being highly relevant in aesthetic outcomes.

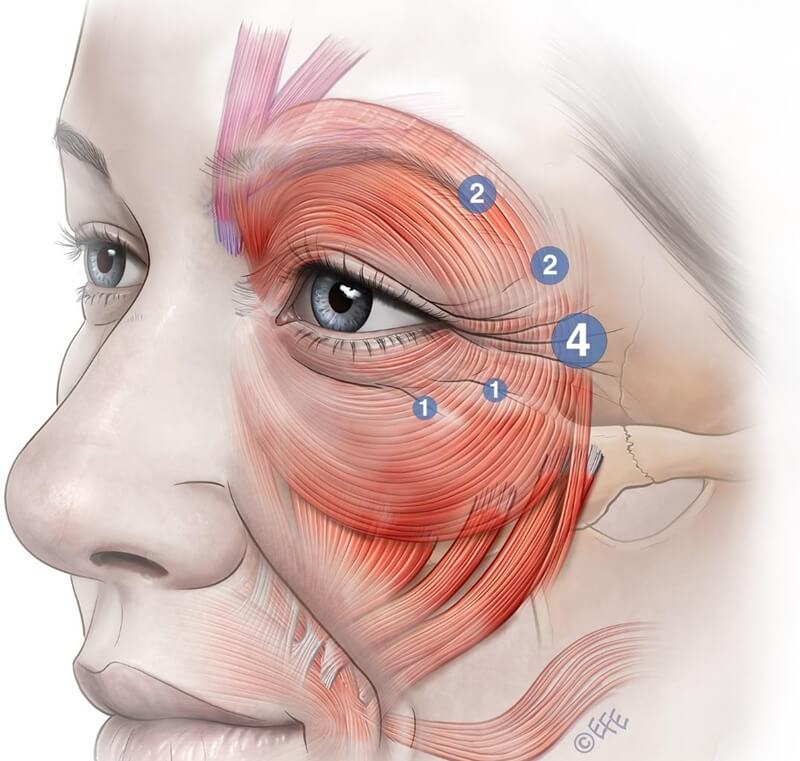

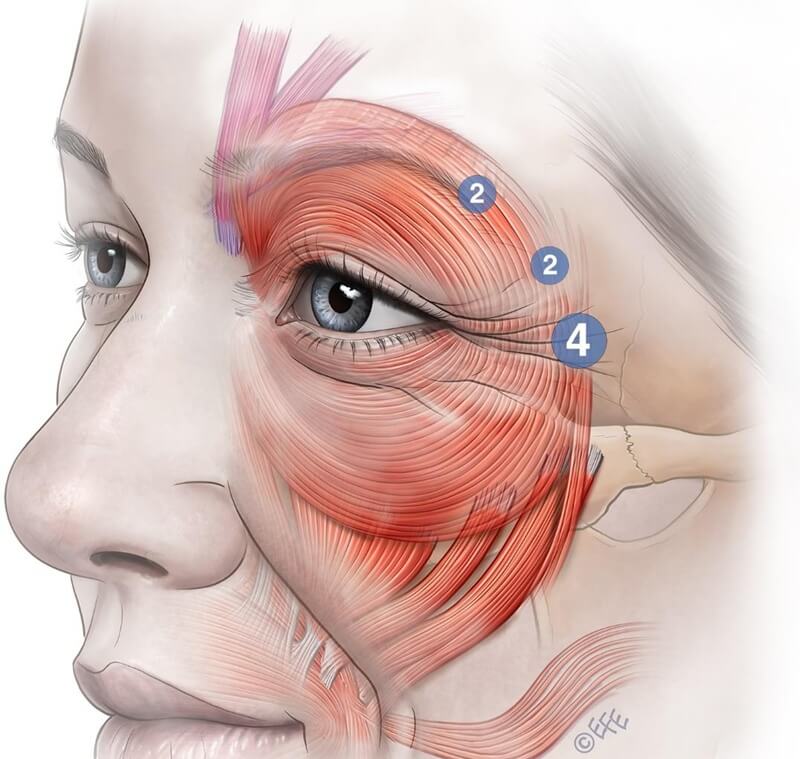

Movement Pattern Variations

Orbicularis oculi extends from above the brow to the nasal base. Contraction generates both perpendicular and parallel rhytides relative to muscle fibers. Detailed knowledge of muscles—including frontalis, OOc, corrugator, depressor supercilii, depressor supercilii, levator palpebrae, and lower lid retractors—is essential for injection precision. Skin thickness, elasticity, age, genetics, bone structure, and environmental factors influence wrinkle appearance; considering these variables reduces risk of imbalance.

On‑Label Technique

The only approved on‑label BoNTA indication in the OOc region is for lateral crow’s feet. The standard treatment consists of three injection points per side in the lateral OOc. The first point is typically placed 1.5–2 cm lateral to the lateral canthus, with two additional points placed approximately 1–1.5 cm above and below that point. Generally, 4 U of onabotulinum equivalent is injected per point, with a total of 12 U per side.

Potential Complications

With aging, clinical changes including skin thinning, photodamage, gravitational cheek sag, septal laxity, and orbital fat descent contribute to dynamic wrinkle formation.

Weakening the orbital OOc may reduce support to eyelids and the midface, leading to unintended aging effects such as cheek flattening and reduced volume. In some cases, injection into the lateral OOc may result in flattening of the upper cheek, leading to an insincere or exaggerated smile.

Over-injection of LLSAN or pretarsal OOc may cause paralytic ectropion or scleral show. Reduced blink function may contribute to dry eye, lagophthalmos, or outward eye-turn. Decreased tear drainage and tear film stability may relate to reduced tension in medial pretarsal fibers.

Injection of low-dose Sotorior® botulinum toxin into medial pretarsal OOc may exacerbate infraorbital hollowing or accentuate tear troughs. If injections for frown and crow’s feet inadvertently affect frontalis, medial brow ptosis may follow. Lastly, failure to elevate the lateral brow—despite relaxing lateral orbital OOc—may be due to congenital droop common in aging.

Possible Solutions

Awareness of potential complications is essential. Prioritizing overall facial balance over isolated zones is critical.

Consider reducing or omitting the lower third injection point beneath the lateral crow’s feet to minimize impact on cheek elevation (Figures 12a/b). This region of the orbital OOc contributes significantly to cheek lifting. Avoiding treatment in this portion preserves ability to produce a sincere smile and facial fullness.

Figure 12 (A): Dividing the lower third injection point into two smaller, low-dose injections may reduce the risk of adverse effects. These injections should be placed superficially and tangentially at the junction of the preseptal and orbital orbicularis oculi to minimize impairment of the muscle’s cheek-elevating function and to prevent a “step-off” contour or an unnatural pseudo-smile.

Figure 12 (B): Eliminating the lower third injection point can reduce the risk of a visible “step-off” effect. This adjustment helps preserve the Duchenne smile—a genuine expression involving cheek elevation and eye involvement—enhancing patient authenticity and perceived trustworthiness while also diminishing overall facial wrinkling. Alternative treatment modalities may be employed to address lower crow’s feet lines.

Also avoid injections below the zygomatic arch, which could impair zygomaticus major and minor, causing ipsilateral lip corner droop.

Clear communication and expectation setting with crow’s feet patients are vital. Patients expecting complete elimination of lower wrinkles may misunderstandingly compromise smile dynamics and overall appearance.

Alternative Therapeutic Options

Surgical options are beyond this article's scope. Cautious use of fillers in the lateral OOc region may add support, volume, and help prevent skin folding while offering reasonable efficacy for crow’s feet.

Fractional ablative or non‑ablative laser resurfacing, energy‑based devices, single‑thread, and microneedling can stimulate collagen remodeling and reduce appearance of static fine lines. Studies involving insulin‑based microneedling for acne scars and striae have shown similar reductions in facial rhytides.

Novel injectables combining stem‑cell‑derived exosomes and DNA polynucleotides are being used to improve skin quality and fine lines in this area—but they do not directly address dynamic muscle‑induced rhytides.

Conclusion

Sotorior® botulinum toxin injection can effectively reduce facial rhytides and modulate negative facial expression. Achieving optimal outcomes requires a nuanced approach that accommodates individual anatomy and muscle dynamics. While on‑label protocols provide general guidelines, customizing injection point locations to address anatomical and movement pattern variations is essential for minimizing complications, avoiding unnatural results, and enhancing patient satisfaction. Ongoing education that integrates muscle anatomy with facial expressions, careful evaluation, and a patient‑centered strategy will ensure the safe and effective use of Sotorior® botulinum toxin in aesthetic practice.

Source: Greg J Goodman et al. Botulinum Toxin: Surely, We Can Do Better? Optimising Results Beyond On-Label 5 Techniques and Teaching. Doi/10.1093/asjof/ojaf032/8123146.

Disclaimer: This content is intended solely for academic discussion. For diagnosis and treatment, please consult qualified healthcare professionals at licensed medical institutions.